This post will delve into trauma-informed practices for research and everyday interactions for library workers. With that in mind, the key concepts from this piece are shared first, to preface the material and ensure you are aware of the content that will be covered up front.

- Trauma is defined by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration (SAMHSA) as “an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”

- Trauma can be experienced by anyone regardless of identities such as gender, age, race, socioeconomic status, and sexual orientation.

- Communities can experience trauma collectively. This can happen through the perpetuation of systemic racism, for example.

- Library workers regularly interact with those who have experienced trauma which can lead to secondary traumatic stress.

- Anyone can heal from trauma, anyone can help somebody heal from trauma, and anybody can, knowingly or unknowingly, retraumatize somebody.

While trauma has always been pervasive in humans, it has become a common topic for discussion in the past few years, particularly since we found ourselves in the midst of a global pandemic and the focus on self care has increased. As with our individual experiences of the pandemic, our individual perceptions of traumatic experiences vary tremendously from person to person. Experiencing trauma can have lasting negative impacts on one’s mental, physical and emotional health. These impacts can then extend beyond the individual to the communities they exist within. Being trauma-informed will help you navigate your work with understanding and compassion for those around you as well as for yourself.

For Our Communities

The understanding of traumatic experiences has developed beyond a single event affecting a single person to also include an event or repeated acts that affect entire communities or generations. Dr. Laura Quiros gives an example of this in her post “How is trauma connected to diversity, equity, and inclusion work?” She writes, “Trauma is at the heart of diversity, equity, and inclusion work because repeated acts of marginalization, oppression and racism are wounds that overwhelm one’s ability to cope.” Therefore, oppression and inequity must be understood as intergenerational traumas for marginalized communities that are still being perpetuated today.

With this understanding, having a trauma-informed approach to your library’s work becomes essential to creating a safe, equitable and inclusive environment. Trauma survivors enter your library regularly and you often can’t tell who has experienced trauma. In many circumstances, blatantly overlooking the trauma somebody has faced, or labeling it incorrectly and misunderstanding it can cause more harm and retraumatization.

For Our Libraries

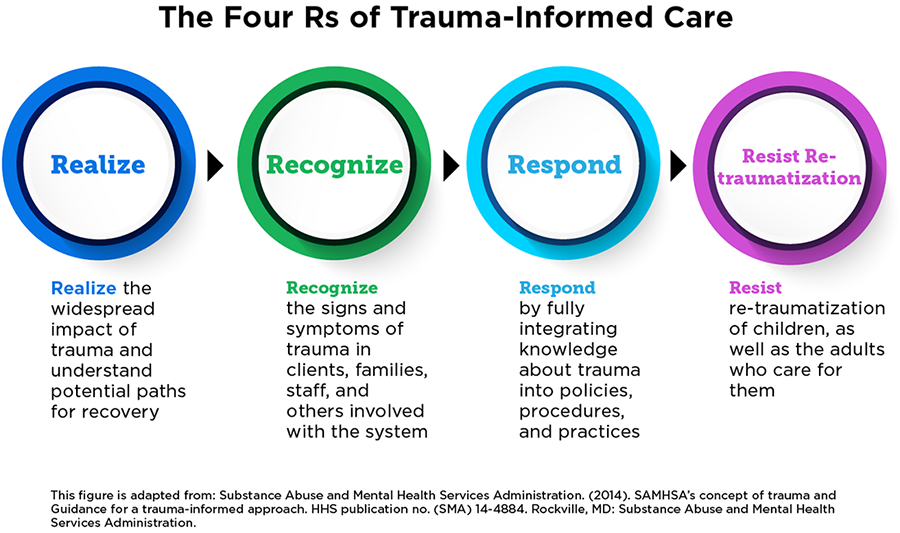

SAMHSA has created frameworks for trauma-informed care and guides for implementing trauma-informed practices which can be found in their Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach report. One of the standard approaches is the four R’s.

Source: Child Trends

Realize that trauma is widespread and has very real effects for individuals and communities. (Around 60% of adults have been found to have been exposed to at least one adverse childhood experience that was potentially traumatizing.)

Recognize the symptoms of trauma and when someone’s actions may be affected by their past trauma.

Respond by implementing trauma-informed practices throughout your organization

Resist retraumatization through actions such as creating a welcoming environment, regulating emotions and offering connection and empathy.

While the four R’s are a great way to outline trauma-informed care, it’s important to have an understanding of how to implement this strategy, particularly for responding and resisting retraumatization.

Even if you understand that your patrons may have experienced trauma it can be challenging to respond appropriately. Experiencing trauma affects one’s perception of the world around them, and may lead to reactive expressions, avoidance, or limited responsiveness, similar to fight, flight or freeze responses. As we move forward with suggestions for a trauma-informed approach to your work, remember that taking care of yourself is of the utmost importance. Setting boundaries and removing yourself from potentially harmful situations to protect yourself from trauma and secondary traumatic stress is always OK.

For Our Research

Incorporating trauma-informed approaches into research is a crucial way to stop data collection from unintentionally harming research participants. While the rest of this post will focus on research through a trauma-informed lens, much of the information is immediately applicable to trauma-informed care in many scenarios including daily interactions with library patrons.

Though you may only have a brief interaction with an individual or group for the purpose of collecting data you can still have a significant effect, whether positive or negative, on their trauma recovery. In research, there is sometimes an attitude that the researcher must be impartial and removed from participant experiences, however, particularly while collecting qualitative data, this is not always the case.

Before interacting with research participants, it is important that you make efforts to properly understand the community you are working with. If you are aware that this community has experienced collective trauma, ensure that you understand the community’s framework, and don’t assign your own labels to what happened. Also, reflect on any social power dynamics that may be at play, and how you can increase the safety and comfort of your participants. As discussed in the LRS post Reading (and Recording) the Room: Focus Groups, creating a safe space is the number one priority for trauma-informed research.

A key way to avoid retraumatization and help others heal from their trauma is through connection and relationship building. Even finding small ways to relate and start a friendly conversation can go a long way. While conducting research, make room for connections and show empathy for your fellow humans. This may involve sincerely acknowledging their hardships and/or offering resources to help somebody through their healing process. Additionally, making your research findings available to research participants whenever possible sustains a relationship of trust and transparency.

Lastly, make sure you regard all participants with respect. If you find that this is not the case, you are probably not the right person to be conducting this research.

For a Survey

To show how these components of trauma-informed care can be directly applied to your research, let’s imagine that you just presented this information as a training session at your library. Now you want to evaluate this training on trauma-informed care by sending out a short survey to participants. Of course, it is possible some of your participants have experienced trauma and so, not only do you want to model a trauma-informed approach to your survey, it is crucial that you do so to actively avoid retraumatizing anyone.

You may create a survey welcome page that looks something like this:

Thank you for your interest in our survey. The purpose of this survey is to evaluate our library’s training on trauma-informed approaches. We will apply what we learn from your responses to our future training and continued improvement of our trauma-informed approach throughout the library. The goal is to help our patrons heal from traumas they may be coping with.

As you move through this survey you can skip any questions you would like or stop the survey completely at any time. The questions will all pertain to your experience at our trauma-informed care training. This survey is completely anonymous, so no personally identifiable information will be asked for. It should take around 5 minutes to complete. If you have any questions or concerns please reach out to us at lrs@lrs.org. You can find additional resources on trauma-informed care and healing from trauma here. Thank you again for your time.

This introduction shares the purpose of the survey, the impact the participants’ responses will have, the content of the survey and the ability survey takers have to skip questions. By explaining all of this, you are empowering participants to make an informed decision on whether they would like to complete the survey and creating a safe space for them to work within.

The survey introduction ends by sharing resources as well as contact information for further questions, comments or concerns. By opening up this line of communication you are offering a way to connect and providing support to anyone interested. Stating the length of the survey and thanking participants shows respect for the participants and their time.

For Recovery

As demonstrated with this post, being transparent and sharing key information from the beginning empowers participants and builds trust. It also lessens the chance that retraumatization will occur if research participants are fully aware and agreeable to what will be discussed beforehand.

Throughout your work, acting with consideration of the traumas your patrons may have faced, including structural inequities, will help to end the perpetuation of these traumas. As community hubs, libraries have the ability to foster connections and be impactful healing spaces. As our understanding of trauma and its effects evolve, our ability to effectively apply trauma-informed care should grow as well.

LRS’s Between a Graph and a Hard Place blog series provides instruction on how to evaluate in a library context. Each post covers an aspect of evaluating. To receive posts via email, please complete this form.