Summer reading programs have long been a staple offering of public libraries’ youth services departments. These programs incorporate strategies to engage young patrons in books, and to develop and maintain reading skills during school vacation. Recently, adult summer reading programs have also become common. Similar to children’s and teens’ programs, these programs engage patrons in reading and dialogue with other readers, and help to promote literacy skills and lifelong learning opportunities.

Spotlight on Adult Summer Reading Programs[note]Findlay, D., & Sinclair, P. (2010), Water Your Mind: Read. 2010 Collaborative Summer Library Program Adult Manual, http://www.cslpreads.org; California Library Association (2010), Adult Summer Reading Program Resources, http://www.cla-net.org/summer-reading/AdultSRP.php#ideas[/note]

Following the lead of summer reading programs for youth, adult summer reading programs tend to be organized around a theme, which guides the development of promotional materials, reading lists, and types of activities offered. The Collaborative Summer Library Program, a consortium of states that works together to develop summer reading program materials for use by public libraries around the United States, began providing themed curriculum for adult programs in 2009. In 2010,[note]The most current year for which summer reading program data is available.[/note] the theme was “Water Your Mind: Read,” which focused on water-related topics (e.g., lawn care, conservation).

Adult summer reading programs include patrons older than 18. In 2010, 41 public libraries in Colorado offered these programs.

Popular adult summer reading program activities include book discussion groups as well as events that relate to the theme. For example, for the 2010 theme, water-themed movie nights and programs on topics such as local water issues and gardening were typical offerings. Libraries also encourage participation by inviting adult registrants to give book suggestions, submit book reviews online, and post online photos of themselves reading or engaging in activities related to the theme. To reward registrants for reading, prizes are typically offered, ranging from materials with the library’s logo, to gift certificates and merchandise from local businesses, to popular consumer technology products such as iPods and netbooks.

Adult summer reading programs benefit both the library and patrons in various ways. In terms of benefits to the library, these programs generate positive publicity; help to promote other library services and programs; increase visits, circulation, and number of registered library cardholders; attract new segments of the population to the library; and strengthen community partnerships.

Benefits for patrons include opportunities for learning and literacy development, as well as exposure to new literary genres. These programs also emphasize the importance of reading to patrons, and promote the idea that reading is fun and reduces stress. In addition, for patrons who are parents or caregivers to children, adult summer reading programs provide opportunities to be involved in common activities with their children, and to model good reading behavior for them.

Prevalence of Summer Reading Programs[note]Comparisons to numbers of programs and registrants in years prior to 2008 are not possible because of a change beginning in 2008 in the way these numbers are reported.[/note]

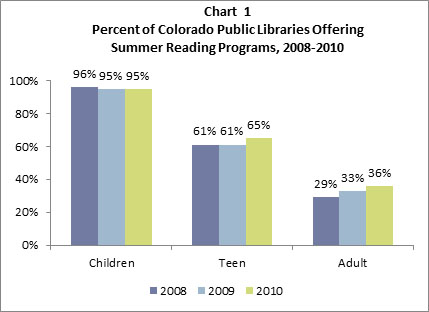

Between 2008 and 2010, almost all public libraries in Colorado offered summer reading programs for children, and close to two-thirds offered these programs for teens (see Chart 1). The number of libraries offering adult summer reading programs rose from 29 percent in 2008 to 36 percent in 2010.

Registrants in Summer Reading Programs

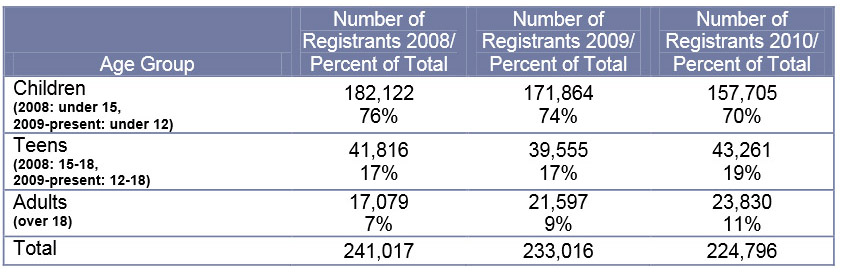

From 2008 to 2010, the percent of summer reading registrants who were children dropped from 76 percent to 70 percent (see Table 1). Teen registrants rose slightly from 17 percent to 19 percent, while the percentage of adult registrants increased from 7 percent to 11 percent. It is important to note that the age range definitions for children and teens changed starting in 2009, which impacted the numbers and proportions for both of these groups (see Table 1 for age ranges).

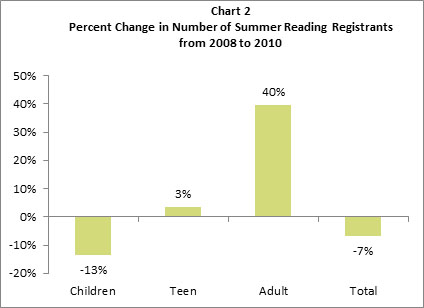

The total number of registrants in summer reading programs decreased by 7 percent from 2008 to 2010 (see Chart 2). This decrease was due to a drop of 13 percent in the number of child registrants. In contrast, the number of teen registrants increased slightly during this time period (3%), while the number of adult registrants increased by 40 percent. The decline in child registrants may be attributed at least in part to the most recent recession (December 2007-June 2009). Shrinking library budgets may have led to several factors that negatively impacted the number of registrants, including closed branch libraries, reduced marketing efforts, and a limited schedule of events. As noted earlier, the change in age range definitions starting in 2009 for children and teens also impacted the numbers of registrants for both age groups. On the other hand, the rise in adult registrants may be due in part to the increased efforts to provide libraries with adult summer reading program resources over the past decade, for example, the Collaborative Summer Library Program’s development of themed curriculum that was mentioned above.

Conclusion

Summer reading programs continue to be popular offerings in Colorado public libraries, particularly for children and teens. Although adult programs are the least prevalent, they have been on the rise from 2008 to 2010, in terms of both the number of libraries offering these programs as well as the number of registrants. As information about adult programs spreads and planning resources become more widely available, it seems likely these programs will continue to grow. An analysis of the statistics reported over the next few years will help to determine whether adult summer reading programs will join their youth counterparts in becoming staple offerings in Colorado public libraries.