A 2008 article in Public Libraries makes the case that there is “no greater need [for library services] than in the lives of incarcerated community members.”[note]Gilman, I. (2008). Beyond books: Restorative librarianship in juvenile detention centers. Public Libraries, 47(1), 59-66.[/note] While the focus of the article is on the role of librarianship in juvenile detention centers, it can be contended that adults in correctional facilities have many of the same needs as their juvenile counterparts, including the need for accountability, competency development, technology instruction, and educational opportunities, all of which contribute to successful reintegration into larger society.

Colorado taxpayers spend $28,759 per inmate per year [note]Rosten, Kristi L. (2008). Colorado Department of Corrections Statistical Report Fiscal year 2007, p. 28. https://exdoc.state.co.us/secure/combo2.0.0/userfiles/folder_18/StatRpt2007.pdf[/note] to house 14,662 state prisoners in its prisons.[note]Colorado Department of Corrections Monthly Population and Capacity Report January 2009. https://exdoc.state.co.us/secure/combo2.0.0/userfiles/folder_15/Current.pdf[/note] That’s an annual price tag of over 420 million dollars. With half of all prisoners returning to prison within 3 years, recidivism reduction has become a statewide priority.

Per Colorado Statute,[note]Colorado Revised Statute 24-90-105.http://www.michie.com/colorado/lpext.dll?f=templates&fn=main-h.htm&cp[/note] the Colorado State Library’s Institutional Library Development (ILD) unit oversees 23 libraries in the state’s 22 adult correctional facilities. As part of its commitment to reduce recidivism, the ILD unit received a Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA) grant to create “Out for Life.” Designed to promote libraries’ role in helping prisoners successfully reenter society, this grant allowed for the purchase of library materials in subject areas that demonstrably reduce recidivism, including job seeking, finding affordable housing, budgeting, addiction recovery, mental health, and recreation.

In cooperation with prison library staff, ILD selected similar materials for each prison library in print and non-print formats and in Spanish and English. Staff at each facility library designed and implemented their own library programs.

To measure the overall success of the grant-funded programs, a survey was administered pre- and post-program to inmates at all but 1 facility, Delta Correctional Center. 3,551 responses were collected, 2,507 pre-program and 1,044 post-program. Responses were compared across facility security levels ranging from Level 1—the lowest security level—to Level V, the highest. Of the respondents, 89 percent of were male and 11 percent female. While 97 percent of respondents took the survey in English, only 3 percent took it in Spanish.

Overview of Results

Individuals who responded after the Out for Life program had been administered in their facilities cited a higher level of helpfulness of the prison library than those who responded before administration of the program (see Charts 1 and 2). Nearly 9 out of 10 (88.6%) respondents reported that they had used the prison library. Notably, in facilities where Out for Life had been administered, a greater percentage of respondents reported using the library to help with the re-entry process. Only 9.8 percent of respondents from post-program facilities reported not using the library, compared with 12.0 percent for pre-program facilities.

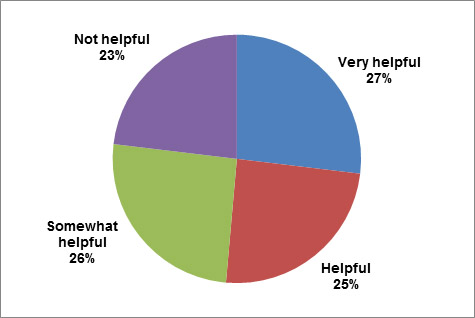

Chart 1: Helpfulness of the Prison Library – Pre-Program Respondents

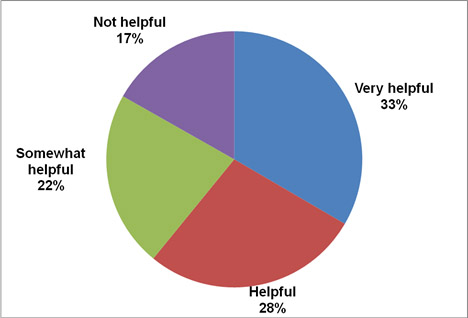

A higher percentage of those who responded after their facilities had completed the program said that the prison library was at least somewhat helpful in preparing them for re-entry, increasing to 83 percent from 77 percent. Furthermore, the percentage of respondents who described the prison library as “very helpful” increased from 26 percent at pre-program facilities to 33 percent at post-program facilities.

Chart 2: Helpfulness of the Prison Library–Post-Program Respondents

Overall, 83 percent of those surveyed after program implementation said that the prison library was at least somewhat helpful in preparing for re-entry, up from 77 percent prior to program implementation. Additionally, 83 percent of all respondents indicated that the prison library assisted in the acquisition of one or more “Life Skills,” which for the purpose of the program included skills related to obtaining employment, public transportation, health care, addiction recovery, mental health services, and education,[note]Walden, Diane (2007). Final report: FY 2006 – 2007 LSTA Grants. Available through the Colorado State Library Institutional Library Services.[/note]as well as managing anger and setting goals.

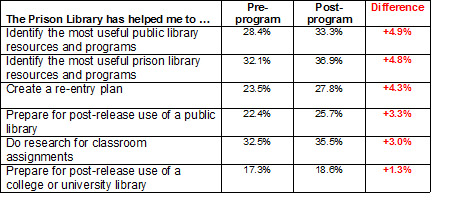

A further breakdown of the responses highlights areas in which the program was most successful (see Table 1).

Table 1: Out for Life

Outcomes for Respondents Pre-and Post-Program (Note: Excludes those who reported that they did not use the library)

(Note: Excludes those who reported that they did not use the library)

Summary and Conclusions

Prison libraries in Colorado are actively engaged in attempting to improve the lives of their constituents, and specifically in helping to ease the re-entry process. This is evidenced by the high levels of satisfaction with the prison library reported by respondents to this survey.

Project Director Diane Walden indicated that the overarching purpose of the Out for Life project was to “provide materials and programs …to support the successful reintegration of Colorado Department of Corrections inmates.”[note]Walden, Diane (2007). Final report: FY 2006 – 2007 LSTA Grants. Available through the Colorado State Library Institutional Library Services.[/note]

While her final report suggests that much remains to be done in order to achieve the project goals, statistical analysis has demonstrated that the project can be deemed a success for many participants, and that inmates in Colorado’s correctional facilities are using library programs and resources in order to aid them in successful reentry.